Recipe Design for Dummies

Hey all,

Without looking, I couldn’t tell you whether or not that sustainability series concluded last week, or whether I subconsciously decided to bail on part 7 of 13, but either way, we’re leaving that dour material in the dust in order to discuss a topic which, given its huge role in brewing and how enjoyable I find it to be, I’m surprised I didn’t write about months ago, namely, what could be argued to be the chief skill of a head brewer or master brewer: recipe design.

While we’ve often looked at the steps in brewing, from mashing to aging, and even some of the more technical details like oxygenation-driven quality loss, we haven’t discussed, and indeed, many non-professional-facing publications or articles daren’t dive into, the reasons you might dial a character malt down from 2% to 1%, or how you pick the exact number of pounds and ounces of malt, or which yeast to even use (since, for example, I’d estimate the number of “British” yeasts available to home brewers at some 40-50, very roughly). And part of that is understandable: it’s complex, somewhat esoteric, and of zero practical use to non-brewers.

So without further ado, here’s a heedlessly detailed walkthrough of the process I recently went through in designing a (potentially terrible!) Golden Ale.

Step One: Research

It would have been conceivable in, say, the 18th century, to pick more or less random amounts of hops and malt, pitch some barm, and make a beer that would have been recognizable as version of something that was available in the marketplace (unless you were one of those American freaks, since they completely eschewed the rules - see George Washington’s absolutely bonkers recipe for wartime “beer”).

But the absolutely astounding number of variations available today, driven in fairly equal measure by the capture of foreign styles (from African Umqumbothi to Belgian Krieks) and endless market-driven natural selection (Fruit Loops Hazy IPA, anyone?), mean that this same “kitchen sink” approach would still work, but only if you limited your malts to lightly kilned base malts (so, no caramel or roasted barley if you’re tossing in loose handfuls), and would only produce a very slim percentage of the full rainbow (though not a tiny list: Saisons, Pale Ales, IPAs, Berliner Weisses, Helles Lagers, Kölsches, Pilsners, Pale Kellerbiers, California Commons, Witbiers, Hefeweizens, Cream Ales, and pale wild fermented beers would all be potential outcomes of this approach).

So what do we do when we want to brew something specific, or something that’s a bit easier to ruin with just a touch of a certain malt, like a Stout or a Czech Dark Lager? In short: we steal.

Why reinvent the wheel when it’s already been honed over the centuries (in the case of some modern styles)? And further, if your customers expect a Hefeweizen to taste a certain way, they may dislike a tasty beer that you call a “Hefeweizen” purely due to your mislabeling it; that’s a common reason for poor performance in competitions as well. So the first place you’d probably want to look for information on a certain style is the veritable Merriam-Webster of beer, the BJCP Style Guide. People normally insert the asterisk here that it’s “not perfect,” or “incomplete,” but I’m hardly a traditionalist, and I’m here to tell you that haters gonna hate, and that it’s absolutely flawless. A polished ruby the size of a tangerine.

While these style guides offer an extensive sensory description of each style, which are certainly useful in making choices regarding yeast and hops, they also offer a limited but incredibly useful set of numbers right off the bat. The style guide for the beer I was designing, for example, a British Golden Ale, lists things like the range of sugar contents (“OG” or Original Gravity), bitterness (“IBU,” International Bitterness Units), color, and ABV (Alcohol By Volume). The first of these, for example, sets limits on the amount of grain I should use for such a beer - too much, and my sugar content is too high, and vice versa.

There are other sources as well, whose utility largely depends on how often people brew the beer you’re planning, I’ve found. For example, there are a million books, clone recipes, and forum discussions on various IPAs (though perhaps, even then, not much on Black IPAs), but if you’re looking for information on a Kottbusser, or the use of guava puree in beer, there may be very little.

Generally, the least I’ll do is see if there’s a Brewers’ Publications book on the style (if I plan to brew a few such beers), leaf through Designing Great Beers, google around for credibly-sourced articles like this one, and maybe do some research on my yeast options, like the style charts on Wyeast’s site (looks like I only have one option!).

For this recipe in particular, I went overboard, and copied down the core statistics of five different credible recipes, in an attempt to suss out the core features of the style. The result was a very specific grain bill and a small number of yeast choices, but a plethora of hopping options (since any hoppy style is likely to produce a range of opinions on varietals and timing).

Step Two: Make Some Decisions

After doing the research, you have to start, you know, actually deciding what to do with it. For this recent Golden Ale recipe, part of my job was easy: the grain percentages were super consistent across recipes (50% 2-Row, 40% Maris Otter, and 10% White Wheat Malt), and the mash temperatures were super consistent (the temperature that you hold the water and grains at so that enzymatic magic can happen).

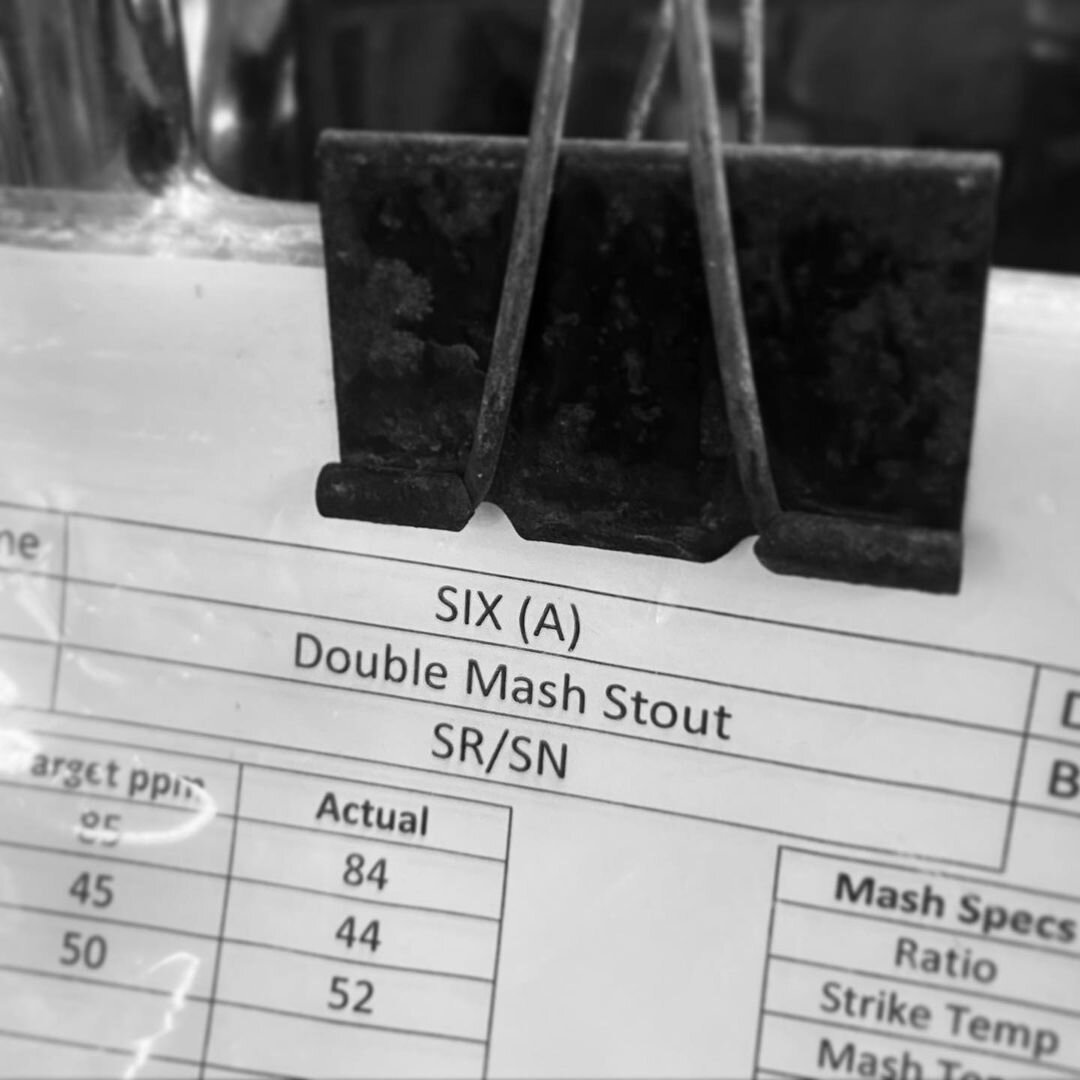

While this beer has a simple grain bill, this task becomes much harder for Belgian trappist beers (with famously elaborate grain bills), some English beers, and in particular Porters and Stouts. The reason for this is pretty simple: if you want flavors from your malt beyond the flavors in base malts (which can be profound), you have to open Pandora’s malt box and consider a huge, huge variety of malts, from the lighter crystal malts (caramel, toffee, toast, say); to darker crystal and specialty malts (with flavors of dark fruit, the beginnings of chocolate, treacle, etc - Special B is a wonderful such malt), and dark malts, like roasted Barley and Chocolate malt. Generally, the darker the grain the lower the percentage you’ll use, but that’s only a very loose correlation. One old recipe for Porter, for example, calls for equal amounts of Pale, Amber, and Brown Malt, which, fun fact, the Maltose Falcons apparently brewed back in 2000.

Further, you might be wondering why this recipe is in percentages and not, say, lbs and oz, and there are many reasons for this, but two spring out immediately: first, I want to be able to slide the gravity up or down without worrying about how many oz I need to add of this and that malt (plus, in looking at five recipes, their sugar contents bounced around, but the percentages of malt were super consistent); second, if I want to scale this recipe at some point from five quarts to five gallons, keeping an eye on percentages minimizes my risk of scaling incorrectly, especially if a large number of malts are at play.

After malt, we have hops, and for this style in particular, to quote from the BJCP style guide:

“Hop aroma is moderately low to moderately high, and can use any variety of hops – floral, herbal, or earthy English hops and citrusy American hops are most common. Frequently a single hop varietal will be showcased.”

In this case, since my first attempt entailed using First Gold hops, which are remarkably on point for this beer, I’ll keep things easy and only use that (though a blend of that and Fuggles and/or EKG would also make perfect sense). This is a classic move for breweries, who might well brew a new recipe based on the hops, malt, and yeast available on hand. Having multiple hoppy beers that overlap in their hop bills is a nice efficient move that minimizes the likelihood of running out of something, plus you get to order in bulk, driving down the price.

The big question, after selecting the hop varietal(s), is how much to add, and when. Broadly speaking, hop additions (to the boil kettle, naturally) that are earlier yield higher bitterness at the expense of less aroma and complex flavor, and vice versa for later additions. After that, you have the option of adding hops at “Whirlpool” (basically the boiled wort once it’s still hot, but down to, say, 185˚F from 212˚F depending on your altitude), or at a number of points during fermentation and packaging. For someone like me, who isn’t terribly partial to hops and thus never really practices writing recipes with them, I’m stuck deferring to the recipes I’m “borrowing” from.

But here, we hit a practical note: I’m not confident that I can add hops to my fermenter without adding a decent amount of (dangerous) oxygen, and, since dry hopping last time may have resulted in a hazier-than-I’d-like Golden Ale (particularly given my yeast choice), I’m ruling out dry hops.

Thus, I chose to defer to a sensible-looking hopping schedule of equal amounts of First Gold at 60 minutes, 10 minutes, and 0 minutes (for a 60 minute boil, that’s right up front, 50 minutes in, and right at the end - hop timings are written in reverse order, in a sense), which gives me a good balance between bitterness from the early addition, flavor and some aroma from the 10 minutes addition, and hopefully a burst of aroma from that late addition. Some variation on this scheme is common for simpler IPAs; it might be 15 or 20 instead of 10, and there might be a dry hopping addition, but that’s a nice skeleton scheme.

As for the quantity of malt and hops, since I’m in the early stages of working out this recipe, I’ve played my usual safe game of targeting the dead-center average of OG (sugar content, which translates to ABV), and IBUs (hop bitterness), in this case an OG of 1.046 (so, 4.6% denser than water), giving an ABV of ~4.5%, and about 40 IBUs, where the range had been 35-45 for the recipes I looked at. Blessedly, this is all kosher as concerns the BCJP guide.

Finally (almost done!), you have yeast selection. Generally, if I have a choice of a few yeasts that are normally used for the style I’m brewing, I’ll look at two things: the general character notes and ester descriptions (so, the flavors of the yeast), and possibly attenuation, which measures the % of the malt sugars that each yeast actually metabolizes (eats). For a drier beer, you might want a higher attenuation, and for a fuller beer, in particular a low-ABV beer like a Dark Mild, you’ll probably want more residual sugars, which you can get in part from a lower attenuating yeast. In my case, I have S-04 on hand (a very common British Ale yeast), so that’s the yeast! Sometimes it’s that easy, and breweries often use one or two strains (ale and lager), with rare exceptions for specialty beers (like Kveik yeasts for Hazy IPAs, increasingly, and sour and Belgian strains for idiosyncratic, yeast-driven beers brewed with them).

Granted, there are some further decisions, like how much CO2 to use, salt use in your brewing water, and whether or not to employ decoctions in your mash for certain lagers, but a lot of such decisions, while important, usually don’t change the beer so much that you can’t pick out the effect of the other variables, broadly speaking, so we’ll breeze right past them (and for this beer, I’ll just be shooting for some safe, average carbonation level, and there aren’t any other tricks or quirks).

Step Three: Plug It Into a Calculator

In the old days, while they’d often write down details of each brew day, in order to work recipes out, they’d brew the same beer a million times, and make changes based on what worked (pre-hydrometer and -thermometer), for example adjusting the amount of malt or water they used to mash, or how long they waited before adding malt (no thermometers, remember?).

Nowadays, you’d be right in guessing that, with the massive variety of styles within breweries, there’s got to be a better way, and indeed, for a few decades now, dedicated brewing software has made recipe design disgustingly easy. I can regularly get sugar concentrations (OGs) within a few percentage points of my target, mash pH readings right on the dot, etc..

Using this software has become very fast and easy. I’ll usually dump in those malt percentages and hop numbers I’d decided above, and then just play around with the ABV, IBUs, mash details, etc, and within a few minutes I have a detailed game plan telling me how many tenths-of-an-oz of each malt to mash in with, how much water to use practically to the milliliter, what temperatures to hit to within a degree, etc..

This process is so simple that there really isn’t much to add. You come into the software with some percentages and broad ideas, and moderate creativity, and you emerge with an obscenely detailed game plan.

Step Four: Brew the Thing, Hope It Doesn’t Suck

Unfortunately, I don’t have enough loose cash to be able to pay someone to brew for me, and, since my PicoBrew is essentially bricked, I have to brew myself, and I have a long history of brewing merely adequate beer. The quality is slowly but surely improving, but it’s worth noting that in the olden days, I could only blame bad recipes for perhaps one in five undrinkable beers; now, it’s closer to four of five or nine of ten, even. Commercial breweries that aren’t very new or very bad don’t really have this problem, it’s worth noting - quite often, their brewing systems produce near-Platonic ideals from their recipes, which is a blessing.

Once you’ve brewed the beer, for better or worse, all you can really do is the obvious: drink it, take a ton of notes (in particular, what you think you might change about the recipe for next time, if anything), give it to other people, record their notes. Competition is an oft-mentioned tool, to this end, for recipe refinement and self-hatred.

Step Five: Adjusting the Recipe

Assuming you want to brew this beer again, and if it’s anything short of a 10/10 beer, you’ll want to first note whether or not there were process issues that damaged the beer, or made perception of recipe subtleties tough or impossible. If process was the singular issue, well, brew it again! Otherwise, if you have changes in mind that might improve the beer, make a small number of guesses, and try again. A note: Changing more than two variables (or perhaps one) is unlikely to yield much information if, yet again, you miss the mark

For example: if the beer was too dry, you’d be a fool to drive down the fermentable sugars by mashing hot, and picking a less attentive (efficient at malt-eating) yeast, and carbonating more or less, and adding flaked oats to your grain bill to add body. Likewise, you wouldn’t want to try brewing a fruited version of your beer while trying to fix the base version, because you’ll never pick up any subtleties of grain character in a Strawberry Milkshake IPA (@ me, I flipping dare you; Hazy IPAs are no better or worse than Orange Peach Mango, Vodka, and Seltzer; I can do this all day). But for my too-hazy first-pass Golden Ale, I wrote the following:

“I’ll probably pull the wheat and maybe the dry hops, and swap the yeast for either Kveik or a dry British ale strain.”

I’ve since decided to keep the wheat (since the yeast I used was popular for Hazy IPAs, which implies that it’s fairly easy to create persistent haze with that yeast; swapping just that may solve the problem, and again, one thing at a time), but I’ve swapped the yeast for another recommended strain, and one likely to be a touch cleaner and clearer, and indeed I’ve pulled the dry hops. Two variables, and fairly distinct ones - that’s a good play.

For beers on a commercial scale, other notes might have to do with timing (when to add dry hops, how long beers take as a note for planning), carbonation levels, and quantities of brewing salts, which is to say, generally subtler variables than a homebrewer might adjust, largely because professional brewers almost universally have more experience and better instincts than homebrewers, which make significantly bad guesses re: malt and hop quantities, hop timing, etc, less likely. If they truly miss the mark, heck, they might just not brew that beer again, which accomplishes the same!

Conclusion

If you hung on through that pitch meeting for BeerSmith, congrats! While I’m sure each brewer designs beers a little differently, I suspect that this process we’ve just gone through is pretty gosh darned close to that of the vast majority of breweries, and if the making of the sausage is something you’re into, well, dinner’s certainly served. Oh, and if you ask me even remotely nicely, you’re welcome to a 10 oz pour of that Golden Ale in, like, four weeks.

Cheers,

Adrian “I need a new hobby” Febre